The EUR ArChal project aims at identifying and analysing, diachronically and transculturally, strategies adopted in the past in the face of global challenges. It thus offers to the scientific community a totally unprecedented basis for knowledge on the subject, while placing the teaching of archaeology at the heart of citizen concerns.

Through building up reference data over the long term and through the plurality of its fields of application, archaeology, at the crossroads of disciplines, contributes to development of new methods adapted to the specificities of ecofacts and archaeological artefacts. This project likewise includes epistemological reflection on the contribution of archaeology to fundamental research and to the socio-economic repercussions of that research.

In a first stage, the methods employed to identify the challenges of the past are examined. While benefiting from the diversity of methods already mastered by research professors and researchers involved in the project, this area will be strengthened by new national and international collaborations. This interdisciplinary approach has proven quite indispensable for global and systemic analysis of archaeological results. The EUR ArChal aims thus at training students in cutting-edge techniques in archaeology, an essential stage in their professionalisation.

Therefore, the project is articulated around four challenges:

Challenge 1: Environment and climate change

Challenge 2: Power and inequalities

-

Challenge 1: Environment and climate change

In the face of the current environmental issues and to actively participate in implementation of strategies for sustainable development, we shall bring together researchers from the natural and archaeological sciences. Although paleoclimatic data increasingly enable us to propose reliable models for ancient climates (e.g., rapidly changing climatic episodes in the Holocene, hydrological crises, poor agricultural years), only a rigorous utilisation of archaeological results will allow evaluation of the impact of climate on the development of societies.

Le zouave of the Alma bridge during the flood of 2018 © France 3 Paris

The Master’s/Doctoral and Seasonal Schools cursus offers diachronic and transcultural insight into major environmental changes that marked the history of humanity. The strategies adopted to cope with these changes are identified and analysed to see which of them were the most efficacious. What was the extent of their repercussions, but also their impact on social, economic and political organisation? To what extent do these strategies reflect the capacities for resilience of societies, communities and individuals? Finally, what is the impact of these changes on collective representations, beliefs, symbols and myths, both yesterday and today?

Subsequently, we take up case studies pertaining to various research areas of the participants (archaeological operations, excavation-site schools, preventive excavations) that will serve us as pilot projects. The students are thus engaged in setting up and implementing all of these (training sessions, subjects of master’s and doctoral dissertations).

As an example, the construction of terraces characteristic of the Mediterranean from the Bronze Age on (around 3000 BCE), has proven to be an effective strategy to fight against erosion due to heavy precipitation in spring and autumn. Today, when there is ever more flooding due to climate change, an international research programme on dating and construction techniques for terraces, linked with a salvage project and development of responsible ecotourism could emerge from this work.

Crop-raising in the rural areas of the Paris Basin during the Iron Age and the Roman Era gave rise to increased soil erosion and the corollary of clogging of a great number of floodplains. The safeguard of wetlands has now become a major issue for safeguarding biodiversity.

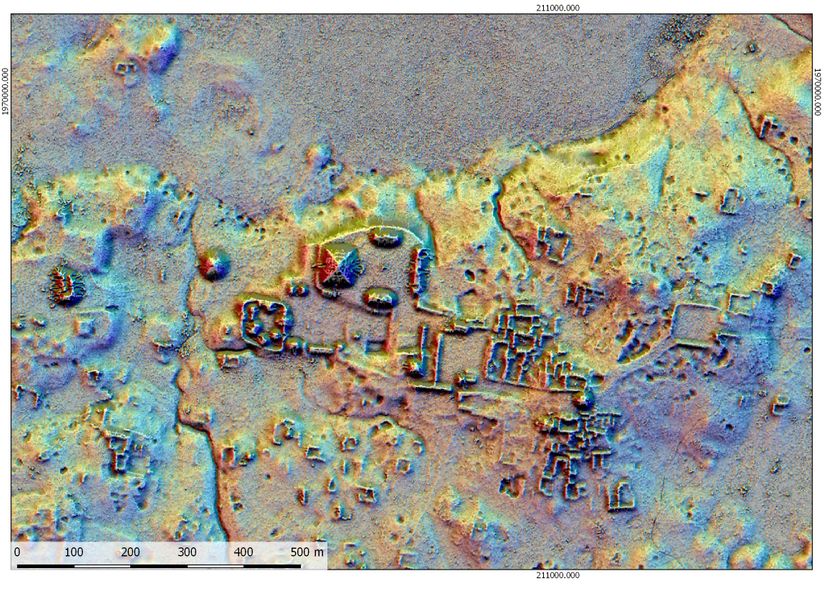

Lidar image of the Naachtun epicentre © Projet Naachtun

Lidar image of the Naachtun epicentre © Projet NaachtunThe ways that the people of Tuamotu (French Polynesia) adapted to an insular environment with very limited resources can provide us with some elements to respond to current ecological challenges in the region. Forests, often perceived as immemorial, have now been revealed through Lidar (laser imaging detection and ranging) to cover many plots, farming structures and habitats. Forest archaeology can thus renew our vision of ecosystem management over the long term, both in fairly low-population areas in France, as well as in Amazonia or Central America, where many archaeological traces of vanished civilisations have been discovered.

-

Challenge 2: Power and inequalities

Borondo, Indigente durmiendo en la calle,Tribulete Street, Madrid, 2011

Photo: Guillermo de la MadridAt a time when reduction of inequalities is a major preoccupation for United Nations member countries (by 2030), the longue durée study of various mechanisms of the emergence and reproduction of inequalities, as well as the strategies developed to reduce them, can offer the community global insight into the subject in an unprecedented way. This will give rise to scientific production, but also to citizen action (lectures, participation in cultural and scientific events) on mechanisms underwriting the reduction of inequalities.

The theoretical framework and methodological tools enabling us to identify inequalities must be presented in a first stage (teaching programs and Summer Schools). This enables us to assess the respective contributions of different results emerging from archaeology (e.g., movable objects, habitat, graves, gestures), physical anthropology (e.g., paleo-pathologies, osteological lesions), iconography and texts.

Through comparative and transversal studies, we then look for the forms that these inequalities take on in different chrono-cultural contexts: during the spread of Homo sapiens, then the adoption of an agro-pastoral economy within the so-called “egalitarian” societies, during the emergence of complex chieftainships, the first attempts at urbanisation and the adoption of state organisation of the royal or imperial type.

-

Challenge 3: Conflicts, mobility and migrations

In our own times, these three major societal challenges – conflicts, mobility, migrations – fuel nationalistic discourse and spread clichés. At the very beginnings of the discipline, archaeology was instrumentalised to support this discourse. In collaboration with various actors in the socio-economic sphere (local communities, heritage institutions, associations) and continuing the work already carried out by members of the EUR, this facet of teaching and research (training weeks, season schools, doctoral seminars) aims at sensitising citizens about the dangers and excesses in such identitarian discourse.

Bringing together archaeologists, anthropologists, historians and epigraphers, a first cycle of teaching (both master’s and doctoral) is dedicated to the diverse forms of conflict attested in various data sources. These is essential to reveal the construction of discourses around conflict, as well as the various representations of it. We shall also evaluate how modern and contemporary conflict archaeology (WWI, WWII, mass graves under Francoism, etc.) can renew our vision of recent historical events. The ethical questions concerning the handling of human and material remains from these contexts will also be dealt with.

A second stage is devoted to voluntary destruction such as arson or pillage, the first archaeological testimony to which goes back to the Neolithic. In today’s world, when “heritage emotions” (D. Fabre) spring forth due to the massive destruction of archaeological sites in the context of Middle East conflicts, what can the past teach us? How were the sites, now destroyed, once managed by the surrounding population? Abandonment, re-occupation, incorporation, or even commemoration, all are important aspects that we must deal with.

Rohingya refugees crossing the border (Bangladesh, 2017)

© HCR/Roger ArnoldYet another stage is dedicated to mobility of people or groups and population shifts. Parameters contributing to various modes of mobility (e.g., conflicts, demographic or climate pressure, the sense of adventure) and migrations are analysed through case studies of various chrono-cultural areas. We also analyse the mechanisms of assimilation, population mixing, rejection or refusal between groups.

-

Challenge 4: Technologies and innovation

This them of research draws on the partners' proven skills in the technological analysis of artefacts (e.g. lithic and bone tools, ceramics, metal), architectural remains (earthen, stone and wooden architecture) and ancient landscape features (e.g., tracks, plots of land, enclosures, cultivated terraces, forests).

Recent advances, particularly in the field of materials characterisation, the study of traces of manufacture and use-wear, and the analysis of ecofacts, require constant methodological development, leading us to call on new technologies (3D microscopy, photogrammetry, Geographic Information Systems, remote sensing). In this respect, we are developing collaborations with specialists, in particular engineers, geologists, geographers, geomaticians and chemists. Lastly, we supervise Master's and PhD subjects with a high potential for technological innovation.

The technological analysis of movable artefacts and structures enables us to reconstruct the methods of invention, dissemination/transfer of techniques, and the learning and transmission of know-how. Emphasis is placed on the notion of innovation, a strategic issue in today's world. While our society seeks the 'immediacy of innovation', archaeological data shows, as do psychology and sociology, that only 'cultural and community judgement' (Gardner 1993) can transform invention into innovation over the long term. Our collaboration with Berlin's Freie Universität and other laboratories specialised in the field guarantees the feasibility of this ambitious project. At a time when innovation is considered to drive sustainable development, what can we learn from the past?

The archaeological record provides us with a multitude of solutions that are “usable” for the future about recycling (for example, amphorae), the valorisation of wild plants (e.g, basketmaking) or waste materials (e.g. agricultural by-products, slag), as well as about alternate uses, or even metamorphoses of places.

-

Methods

The EUR's teaching project aims to promote training that is as close as possible to current methodological developments in cutting-edge research and innovation, particularly in methods for analysing archaeological remains using new technologies.

Emphasis is placed on training in methods for acquiring and processing archaeological data using the digital tools of digital archaeology.

The areas concerned are:

- Prospecting and survey techniques (topography and production of digital terrain models and archaeological stripping surveys using laser tacheometers, differential GPS, drones and tripod-mounted laser scanners).

- Recording and processing data on artefacts (archaeological, geographical and collection information systems, statistics and digital processing).

- Microscopic and physico-chemical analysis methods to characterise materials, ecofacts (carpological and osteological remains), traces of wear (binocular magnifiers, optical and confocal microscopes, Scanning Electron Microscope- SEM), elemental analysis methods (X-ray diffraction, microscope with electron microprobe analysis).

- Image analysis, 3D modelling and 3D printing (photogrammetry, lasergrammetry and 3D printing)

The use of digital technologies is essential for sharing and disseminating knowledge. At our EUR, these technologies are taught through methodological workshops based on practice and interactivity.